Where was Abraham Davis in 1777?

This is the 5th article in a series about Revolutionary War hero Abraham Davis (abt 1740-1792) — my 5th great-grandfather.[1]Click HERE to begin the series, all filed in Homan Ancestry folder.

As a reminder, beyond official military records, there are two main sources for Abraham’s war story:

- An Autobiography written in 1830s by Abraham’s grandson, George W. Davis (1797-1853).[2]George W. Davis, “Autobiography;” letter, circa 1835 (Gonzales, Texas); privately held by Daniel Spitler, Phoenix, Arizona, 2024. [Typewritten transcript, date unknown, of hand-written letter to … Continue reading

- A Research Summary prepared in 2022 by Trevor Quasius and Noah Caplan of the Monmouth Battlefield Visitor Center.[3]“Research summary – Abraham Davis,” Trevor Quasius and Noah Caplan, research staff, Monmouth Battlefied Visitor Center, Monmouth, New Jersey, August 2022, provided to Daniel Spitler, … Continue reading

I refer to them as the Autobiography and Summary.

So far we’ve established that Abraham Davis probably served in the 1st New Jersey regiment from 1775 to 1776, and definitely served as a privateer operating out of Chestnut Neck, New Jersey in 1778, 1779, and plausibly 1780.

But where was Abraham Davis and what was he doing between those two periods? One possibility is that upon discharge from 1st New Jersey regiment in November 1776, he simply returned to Chestnut Neck, tended to his family and personal affairs, and began privateering with “brother-in-law” David Stevens at some point in 1778.[4]I have been characterizing David Stevens as Abraham’s brother-in-law. Actually he was Abraham’s uncle-in-law. Stevens married Amy Smith, a sister of Abraham’s mother Ruth Smith … Continue reading

On the other hand, the Autobiography claims that —

“(My grandfather) was in the well-fought battles of Princeton, Monmouth, and Redbank in New Jersey.”[5]Davis, “Autobiography,” 3

Notice that these three battles fit neatly into the time window between Abraham’s service in 1st New Jersey and his privateering career.

- 5 Nov 1775 Enlists in 1st New Jersey

- Nov 1776 Discharged from 1st New Jersey

- 2 Jan 1777 Battle of Princeton

- 22 Oct 1777 Battle of Redbank

- 28 Jun 1778 Battle of Monmouth

- 16 Jul 1778 David Stevens obtains Letter of Marque for sloop Chance

- August 1778 Capture of Venus of London

- 6 Oct 1778 Battle of Chestnut Neck

- 7 Jun 1779 Abraham Davis obtains Letter of Marque for Fly

- 17 Sep 1779 Abraham Davis obtains Letter of Marque for Hornet

Upon examining these claims, the Summary points out —

There are no military records available that place Abraham Davis at the battles of Princeton, Red Bank, or Monmouth.[6]“Research summary – Abraham Davis,” Quasius, 2022.

The Summary doesn’t dismiss the possibility that Davis was present, but simply underlines the lack of proof. In fact, Quasius and Caplan are correct: no records have been found which place Abraham Davis by name at those battles.

New Information

However, I discovered two full pages focused exclusively on Abraham Davis tucked away in an appendix of a book I just bought — A Nest of Rebel Pirates.[7]Franklin W. Kemp, “A Nest of Rebel Pirates,” 2nd edition, p. 190 (Batsto, New Jersey: Batsto Citizens Committee, 1993); 1st edition published 1966. The author, Franklin W. Kemp, also became aware of the Autobiography and obviously did some research based on that. Here’s his key sentence:

Abraham Davis served as an ensign and lieutenant in Captain George Payne’s Company, Third Regiment, Gloucester County Militia in 1777, and later as a captain in the same regiment.[8]Kemp, “A Nest of Rebel Pirates,” 190.

Although Kemp does not provide citations, I suspect he based his statement on the pension files of former Gloucester County Militia soldiers. For example, the 1832 pension application of Davis Denike states:

I joined the (3rd) battalion in Chestnut Neck in Spring 1777 when George Payne was the captain and Abraham Davis the lieutenant.[9]Davis Denike pension file, S. 2172, 1832; digital images, “U.S., Revolutionary War Pensions 1800-1900,” Fold3 (www.fold3.com : accessed 7 May 2025), p. 4; citing NARA RG 15, publication … Continue reading

Kemp further states that Abraham Davis received a depreciation-of-pay certificate for £2:15:5 after the war.[10]Kemp, “Rebel Pirates,” 190.

I need to find the depreciation-of-pay record and more fully review the pension applications of former Gloucester County Militia soldiers. Nonetheless, I think we can safely conclude that Abraham Davis was a member of the 3rd Battalion, Gloucester County Militia. Indeed, he was an officer. I presume Abraham joined in late November or early December 1776 upon leaving the 1st New Jersey and was promptly made Ensign because of his military experience. By April 1777, he was promoted to Lieutenant.

More importantly, it means there is a decent chance that Abraham Davis was present at the battles of Princeton, Redbank, and Monmouth, as his grandson claimed.

3rd Battalion, Gloucester County Militia

The 3rd Battalion, Gloucester County Militia was led by Col. Richard Somers and comprised up to 250 men from the eastern part of Old Gloucester County, specifically Galloway and Great Egg Harbor townships.[11]The Col. Richard Somers Chapter of the Sons of the American Revolution is a local organization that maintains the history of this outfit and honors its traditions. Militia units were separate from the Continental Army and led by state-level commanders. Gen. Washington did not have direct control of the militias but coordinated with their commanders as best he could.

The role of the 3rd Battalion — or Egg Harbor Guard — as it was sometimes known, was to patrol the coast, provide intelligence on British movements, guard against Tories, harrass British shipping, and serve as an auxiliary land force when necessary. I believe that most if not all privateers and crewmen who resided in the Egg Harbor area were members of the 3rd Battalion, Gloucester County Militia. If so, that shines new light on why Abraham Davis was called a Lieutenant under David Stevens and later a Captain. This wasn’t just naval terminology. These were his actual military ranks in the militia. It might also explain why the Autobiography made such a point about Abraham holding captain rank, even if it had the unit affiliation wrong.

In its role as an auxiliary land force, the Col. Somers 3rd Battalion came to the defense of the Continental Army when it faced annihilation in December 1776; it supported Fort Mercer when it was threatended in October 1777; it supported the Continental Army in June 1778 at Monmouth Courthouse.

Let’s take them one by one.

Battle of Princeton

As historical background, the 90 days from mid-November 1776 to mid-January 1777 are arguably the most critical period of the entire war. After the fall of New York City on 16 November 1776, the Continental Army was swiftly pushed out of New Jersey and sought refuge on the Pennsylvania side of the Delaware River. Gen. George Washington was losing the confidence of Congress and many citizens. There were whispers he might be replaced. But, in a bold stroke, Washington stunned the world by crossing the Delaware River in a snowstorm on Christmas Day 1776 and captured the Hessian garrison at Trenton, thereby saving the Revolution.

Washington followed this up with a stand at Assunpink Creek on 2 January 1777 and, most especially, a huge victory at Princeton on 3 January. The period from 25 December 1776 to 3 January 1777 is referred to as the Ten Crucial Days of our Revolution.

One reason for the success of the Ten Crucial Days was the part played by state militia. In November and December 1776, the Continental Army was not only retreating, but shrinking. Soldiers whose one-year term of enlistment was expiring were leaving and others were deserting. Until the army’s regiments could be reconstituted, Gen. Washington called upon militias to come to his rescue.

One of those who responded was Virginia Col. Samuel Griffin who cobbled together a combined militia force of 800 men from his home state, Pennsylvania, and New Jersey, including 200 or so from Col. Somers 3rd Battalion. Based on pension applications, we know that Capt. George Payne‘s company, the one to which Abraham Smith was assigned, was part of this campaign. I assume Abraham was an Ensign at that point.

Delaware River above Philadelphia during Revolutionary War (hexasim.com)

To capture Trenton, Washington needed to hamper the ability of the garrison at Bordentown, 7 miles downriver, to come to its defense. Col. Griffin’s task was to draw the Hessians out of Bordentown, so he maneuvered his militia closer and closer, arriving at Mt. Holly on 17 December 1776. One Gloucester pensioner remembered —

The company marched from Egg Harbor to Haddonfield … and (then) marched to Mt. Holly.”[12]Earl Cain, “The Revolutionary War in South Jersey,” Col. Richard Somers Chapter, Sons of the American Revolution, powerpoint, 20 January 2020, 4 (www.colrichardsomers.com : 20 April 2025); citing … Continue reading

The ruse worked. Col. Carl von Donop brought his battalion out to face the militia threat. On 22 and 23 December 1776, the Hessians and American militiamen fought two small-scale engagements known as Petticoat Bridge Skirmish and Battle of Iron Works Hill. Two or three Egg Harbor men died, names unknown, and privates Stephen Ford and Simon Lucas were wounded.[13]Rev. Norman R. Goos, “Carefully Planned Distractions Create Opportunities for Surprise Victories,” Yearbook of the Atlantic Heritage Center, Somers Point, New Jersey, 2010-2011. In occupying Mt. Holly on 23 December 1776, the Hessians were now 18 miles from Trenton, not seven. Gen. Washington received the news on 24 December, thereby sealing his decision to cross the Delaware.

Petticoat Bridge Plaque (Wikimedia)

Inexplicably, Col. von Donop kept his regiment in Mt. Holly three more days until he heard the shocking news of the British defeat at Trenton. It is said that he became infatuated with a beautiful young widow in town and was reluctant to depart!

A couple days later, British Gen. Cornwallis was fast approaching the Delaware River seeking revenge. Griffin’s militia force, now under the command of Gen. John Cadwalader, was ordered to directly support Washington. After a forced night march, Cadwalader arrived at the battlefield south of Trenton on the morning of 2 January 1777, just in the nick of time for the Battle of Assunpink Creek. The Battle of Princeton occurred the very next day, 3 January 1777.

In both battles, the American militia operated primarily in reserve, and as far as I can tell, was never on the front lines. Nonetheless, they still witnessed some action. Egg Harbor private Forrest Belangy died after his leg was shot off by a cannonball at Assunpink Creek.

After Princeton, Col. Somers 3rd Battalion separated and went in three different directions. Two companies headed back to Little Egg Harbor to protect the coast, one headed to Burlington, and two more, including Capt. Payne’s, remained with the Continental Army.

The soldiers under Capt. George Payne and Capt. David Weatherby spent the winter with Washington and the Continentals in Morristown.[14]Cain, “The Revolutionary War in South Jersey,” 8.

George Washington by Charles Wilson Peale, 1776

It’s pretty cool to imagine that Abraham Davis must have seen George Washington in person.

To summarize, Abraham Davis did not participate directly in Washington’s famous Crossing of the Delaware, but was part of a militia regiment which contributed to the success of the assault on Trenton. He then would have been present at the Battle of Assunpink Creek and Battle of Princeton, and followed that up by traveling with the main army to its winter encampment at Morristown, New Jersey.

Battle of Redbank

It took them awhile, but the British finally captured Philadelphia on 26 September 1777. To prevent British ships from sailing up the Delaware River to resupply the city, Washington ordered two river forts just south of Philadelphia be reinforced and strengthened — Fort Mifflin and Fort Mercer.

On 22 October 1777, America successfully defended Fort Mercer in the Battle of Redbank, decimating Col. von Donop’s Hessian regiment in the process (and killing von Donop himself). Although the battle involved about 2,400 Hessians facing 400 or so defenders, estimated casualty losses were amazingly lopsided: 40 American, 514 Hessian, in a battle that lasted less than an hour. Over 100 Hessians lay dead on the field, dozens more died later of wounds. Only 14 Americans were killed.

The defending soldiers inside Fort Mercer were two Rhode Island regiments led by Gen. Christopher Greene. Approximately 400 Gloucester County militia were initially inside as well, but after Greene shrunk his defensive perimeter, he released the militia to harrass and snipe at the Hessians and burn local bridges. He specifically dispatched Felix Fisher’s company to Cooper’s Ferry to report when the British crossed over.[15]James R. McIntyre, “Chapter Four: The Delaware River Campaign of 1777,” On Contested Shores: The Evolving Role of Amphibious Operations in the History of Warfare (Marine Corps University … Continue reading

So what was the role of Col. Somers 3rd Battalion? It’s hard to say exactly. One or more companies were probably in the fort before the battle, or were part of Gen. Silas Newcomb‘s force of New Jersey militia that hovered close to the battlefield, or both. Capt. Joseph Conover’s company is known to have arrived from Little Egg Harbor the day after the battle and assisted in the gruesome task of burying Hessians in mass graves.[16]“Col. Richard Somers’ Atlantic County Regiment October 1777,” powerpoint pdf, 13; Colrichardsomers.com (www.colrichardsomers.com : 17 May 2025); citing pension application of Levi … Continue reading

Although speculative, there is another scenario in which Abraham Davis might have participated in the Battle of Redbank. A flotilla of American ships and row galleys populated the Delaware River below Fort Mercer and successfully kept British warships from supporting the attack. The row galleys played an important role in enfilading the Hessians with grapeshot as they stormed the fort, significantly contributing to the scale of the losses.

This flotilla included Pennysylvania and New Jersey “naval militias” as well as Continental Navy warships. Was Col. Somers 3rd Battalion sometimes considered a naval militia? I doubt it, but since many of the men were involved in privateering, I think it’s at least conceivable that Abraham Davis and other Egg Harbor guardsmen operated one of the smaller vessels or helped crew a ship.

Battle of Monmouth

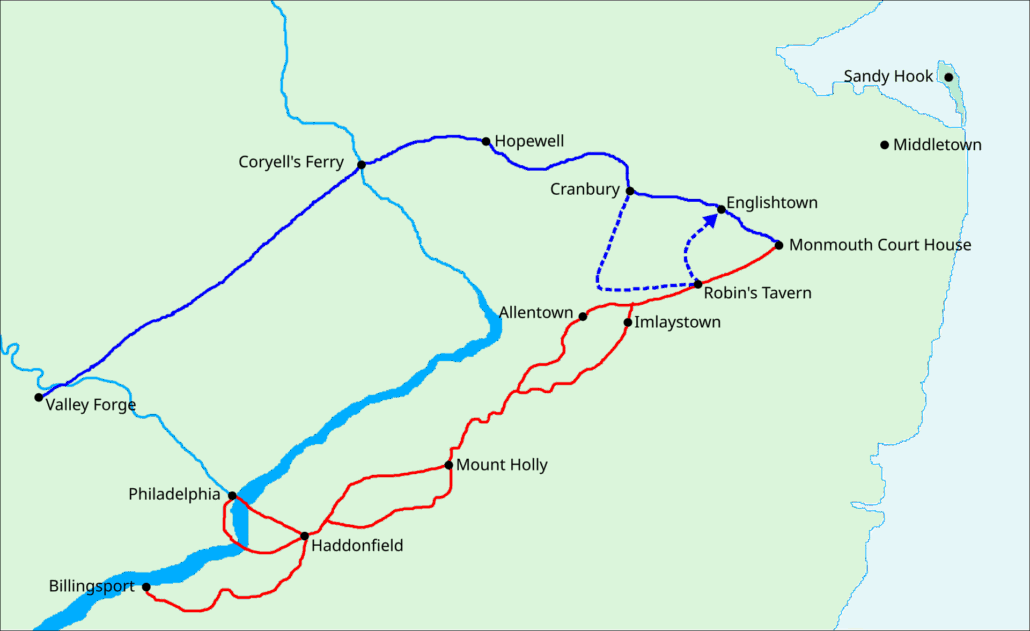

France’s entry into the war on the side of the United States in early 1778 altered the strategic balance of power. It was now untenable for Britain to maintain its occupation of Philadelphia because of the threat of the French Navy. London ordered Gen. Henry Clinton to reposition the British army. His 15,000 troops abandoned Philadelphia on 18 June 1778 and marched through northern New Jersey toward Sandy Hook, where the troops boarded ships for the final leg to New York City.

Washington asked the New Jersey militia to delay the British advance as much as possible, while he moved his own army closer in hopes of an opportunity to attack the British rear.

That chance came on a hot, sweltering day at Monmouth Courthouse on 28 June 1778. Washington’s advance wing under Gen. Charles Lee moved against the British rear about 8:00 in the morning and a long day of combat began, with Washington himself showing up about noon to take over. Tactically the battle was a draw. However, because the British abandoned the field that night — they were, after all, trying to get to New York City — Washington was able to characterize it as a victory and Congress echoed the sentiment.

Approximately 1,000 New Jersey militiamen were involved in the battle. They augmented the New Jersey Brigade of Gen. William Maxwell, which in turn was one of the main units of Lee’s advance force. Thus, the militia were participants throughout the day. Gloucester County militia were present, but it is nearly impossible to identify which specific companies or individuals.

Conclusion

We cannot prove that Abraham Davis was present at the battles of Princeton, Redbank, and Monmouth. However, we can by deduction argue that it is very likely he was present at Princeton, probably was involved in militia activities associated with the Battle of Redbank, and could have been at Monmouth.

Lastly, I find the close timing of the Battle of Monmouth on 28 June 1778 and the date of David Stevens first Letters of Marque on 16 July 1778 suggestive. That’s because Chestnut Neck pretty much shut down during the British occupation of Philadelphia, September 1777 – June 1778.

… the privateer base of Little Egg Harbor temporarily wilted.[17]Donald Grady Shomette, Privateers of the Revolution: War on the New Jersey Coast 1775-1783 (Atglen, PA: Schiffer Publishing, 2016), 131.

However, as soon as the British left, privateering out of Little Egg Harbor promptly boomed once again. Assuming Abraham Davis was at Monmouth on 28 June, I can imagine him returning home and immediately hooking up with in-law David Stevens to become a privateer by mid-July (as discussed in previous posts). In other words, the timing corresponds well with the known history of New Jersey privateering. Thus, Captain David Stevens and Lieutenant Abraham Davis were able to engage in a highly successful and lucrative career as privateers, beginning with the sloop Chance.

References

| ↑1 | Click HERE to begin the series, all filed in Homan Ancestry folder. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | George W. Davis, “Autobiography;” letter, circa 1835 (Gonzales, Texas); privately held by Daniel Spitler, Phoenix, Arizona, 2024. [Typewritten transcript, date unknown, of hand-written letter to author’s offspring, passed down through the Davis family.] |

| ↑3 | “Research summary – Abraham Davis,” Trevor Quasius and Noah Caplan, research staff, Monmouth Battlefied Visitor Center, Monmouth, New Jersey, August 2022, provided to Daniel Spitler, Phoenix, Arizona. |

| ↑4 | I have been characterizing David Stevens as Abraham’s brother-in-law. Actually he was Abraham’s uncle-in-law. Stevens married Amy Smith, a sister of Abraham’s mother Ruth Smith in 1772. The term brother-in-law was more flexible 250 years ago. See Daniel Smith Lamb, “Genealogy of Lamb, Rose, and others” (Washington, DC: Beresford Printer, 1904, 95. |

| ↑5 | Davis, “Autobiography,” 3 |

| ↑6 | “Research summary – Abraham Davis,” Quasius, 2022. |

| ↑7 | Franklin W. Kemp, “A Nest of Rebel Pirates,” 2nd edition, p. 190 (Batsto, New Jersey: Batsto Citizens Committee, 1993); 1st edition published 1966. |

| ↑8 | Kemp, “A Nest of Rebel Pirates,” 190. |

| ↑9 | Davis Denike pension file, S. 2172, 1832; digital images, “U.S., Revolutionary War Pensions 1800-1900,” Fold3 (www.fold3.com : accessed 7 May 2025), p. 4; citing NARA RG 15, publication M804. |

| ↑10 | Kemp, “Rebel Pirates,” 190. |

| ↑11 | The Col. Richard Somers Chapter of the Sons of the American Revolution is a local organization that maintains the history of this outfit and honors its traditions. |

| ↑12 | Earl Cain, “The Revolutionary War in South Jersey,” Col. Richard Somers Chapter, Sons of the American Revolution, powerpoint, 20 January 2020, 4 (www.colrichardsomers.com : 20 April 2025); citing Zadock Bowen pension application, NARA RG 15, publication M804. |

| ↑13 | Rev. Norman R. Goos, “Carefully Planned Distractions Create Opportunities for Surprise Victories,” Yearbook of the Atlantic Heritage Center, Somers Point, New Jersey, 2010-2011. |

| ↑14 | Cain, “The Revolutionary War in South Jersey,” 8. |

| ↑15 | James R. McIntyre, “Chapter Four: The Delaware River Campaign of 1777,” On Contested Shores: The Evolving Role of Amphibious Operations in the History of Warfare (Marine Corps University Press, 2020), 62. |

| ↑16 | “Col. Richard Somers’ Atlantic County Regiment October 1777,” powerpoint pdf, 13; Colrichardsomers.com (www.colrichardsomers.com : 17 May 2025); citing pension application of Levi Price. |

| ↑17 | Donald Grady Shomette, Privateers of the Revolution: War on the New Jersey Coast 1775-1783 (Atglen, PA: Schiffer Publishing, 2016), 131. |